I spent some time over the holiday break updating and adding to my long-running photo series of Detroit neighborhoods as captured (primarily) by Google Street View, called GooBing Detroit.

GooBing is a collection of photographs-of-photographs that I’ve curated since 2012. Initially, I used GooBing Detroit to document the physical consequences of tax foreclosure in Detroit, though the most recent Street View imagery helps address new topics.

Google Street View, as well as the City of Detroit’s own fantastic street view program with imagery published via Mapillary, now contains a citywide “frame” in the stop-motion street view history of Detroit for 2022.

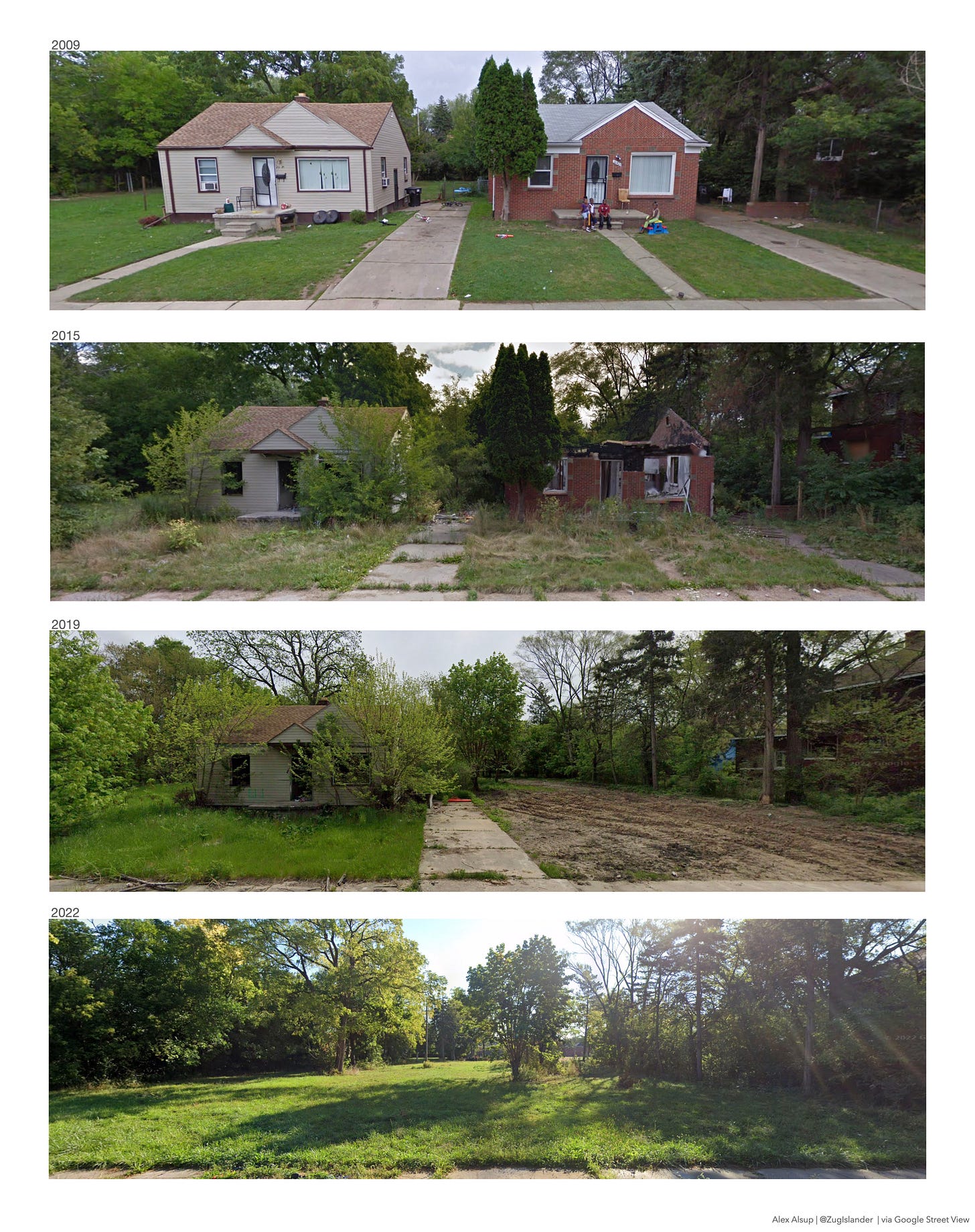

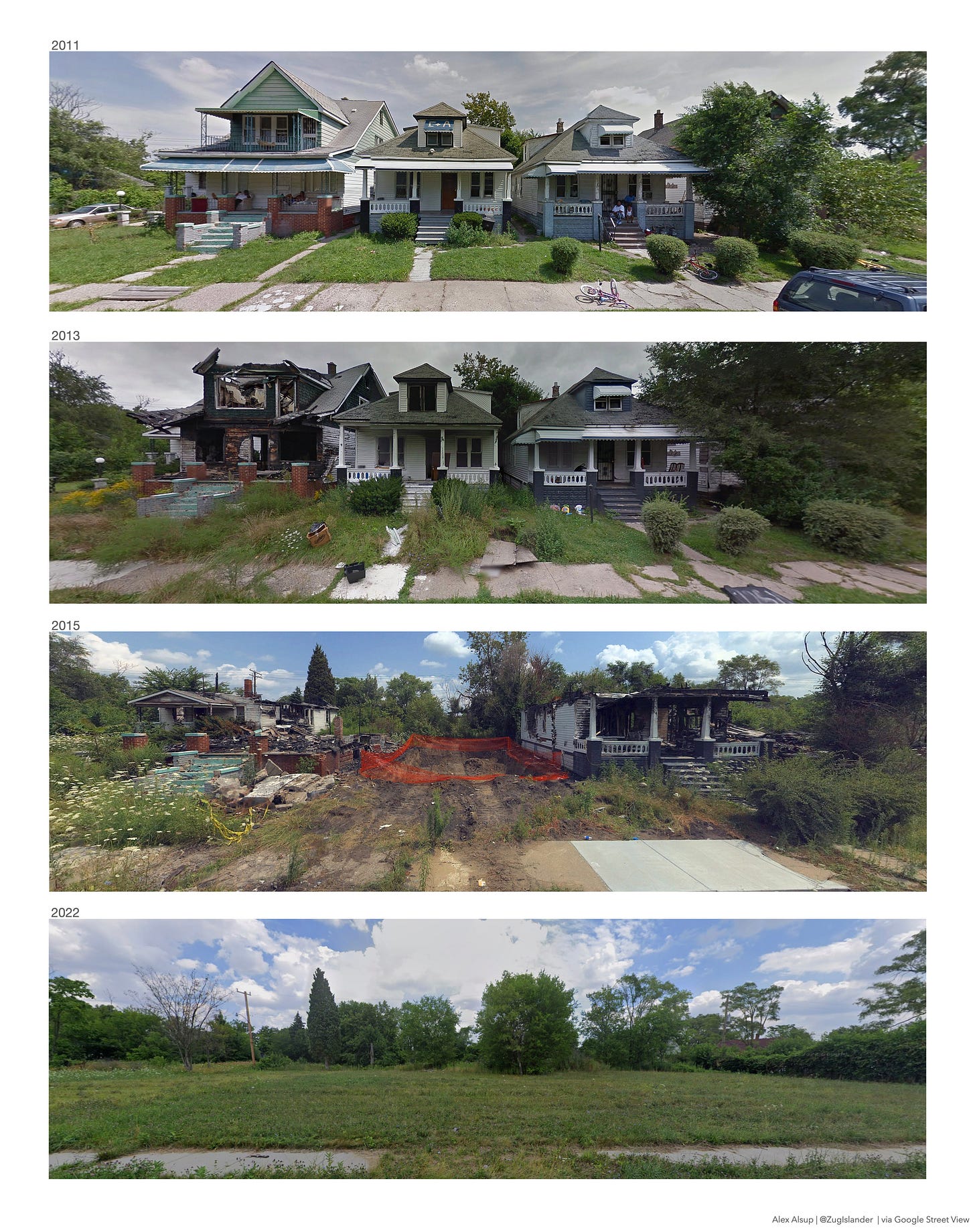

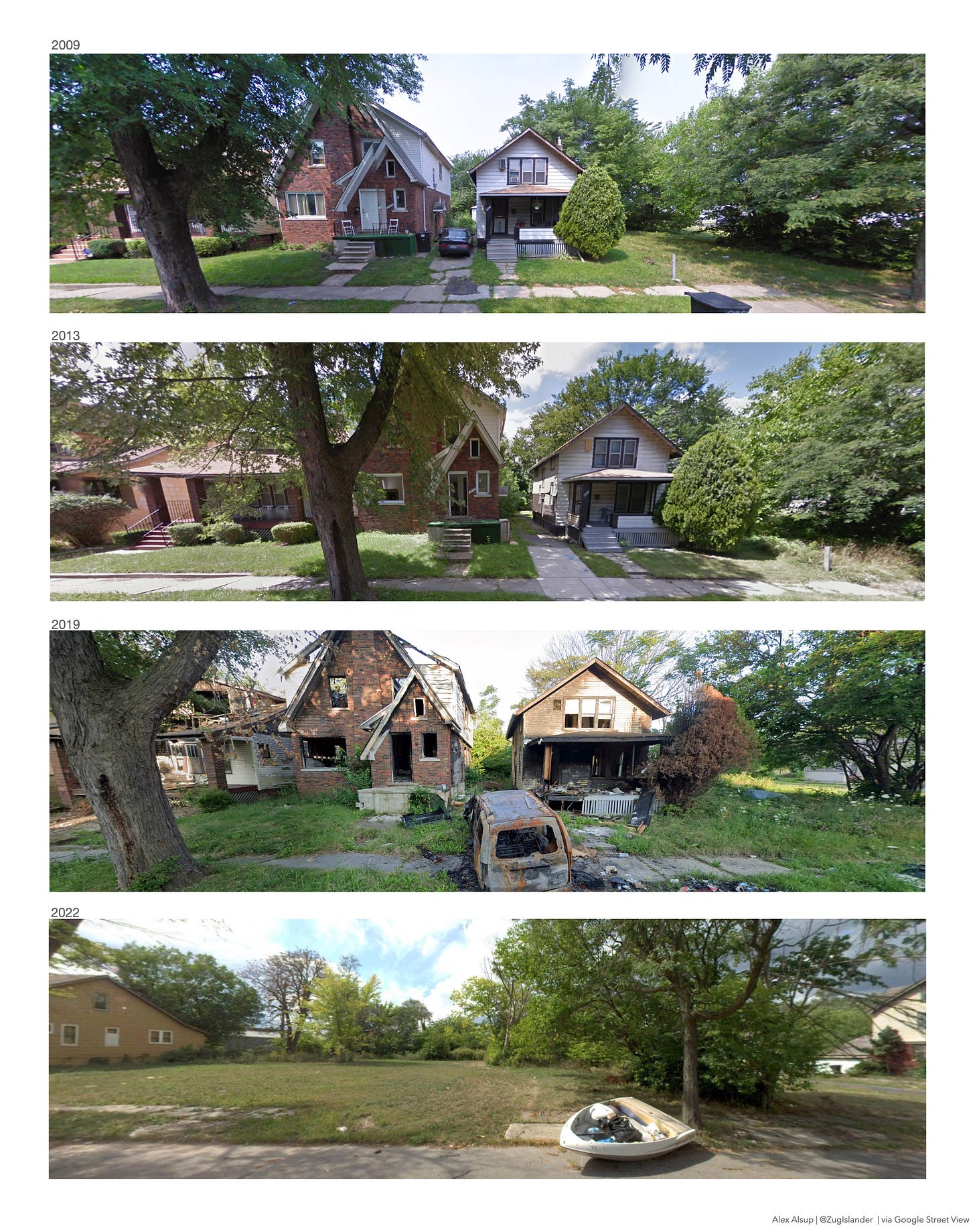

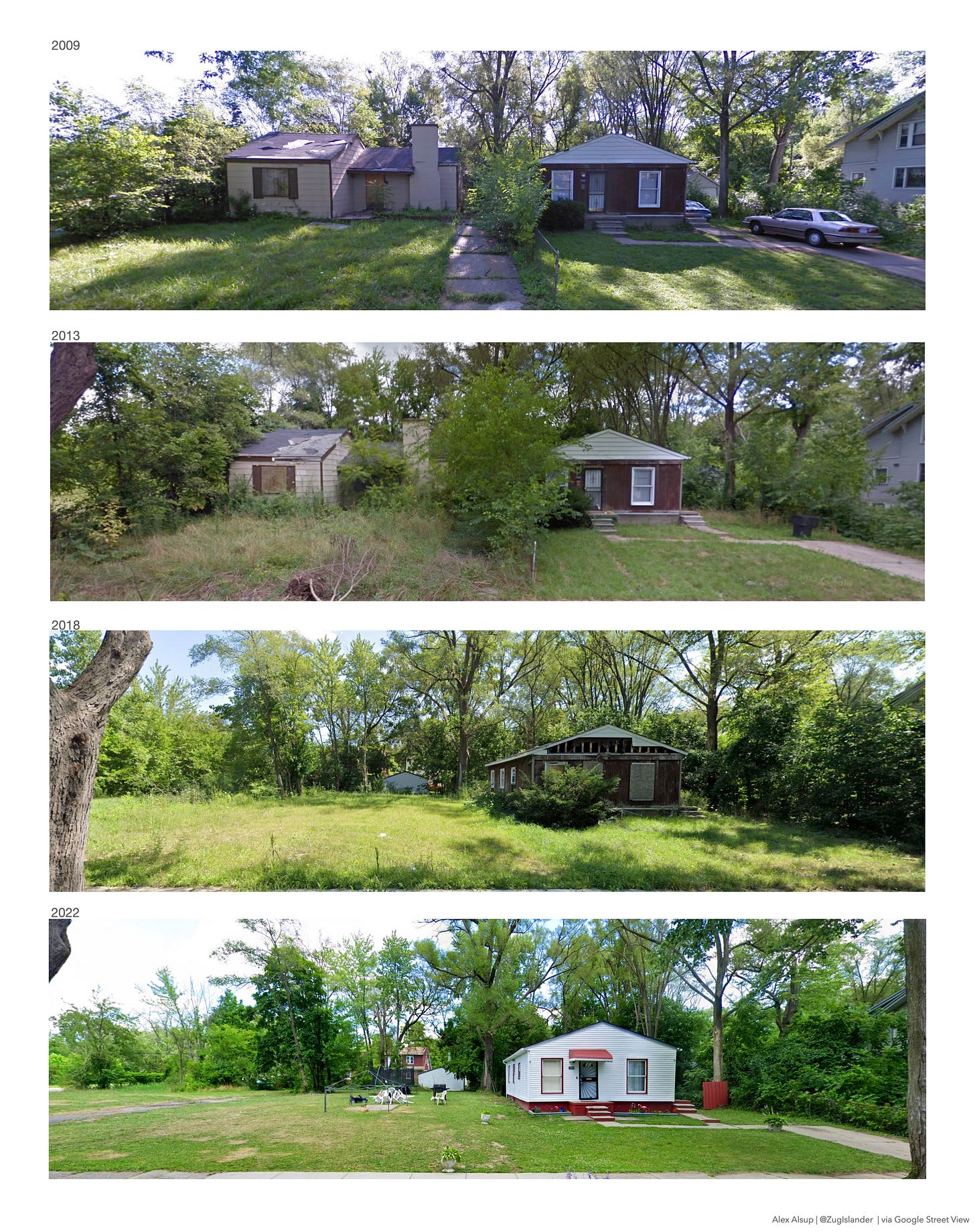

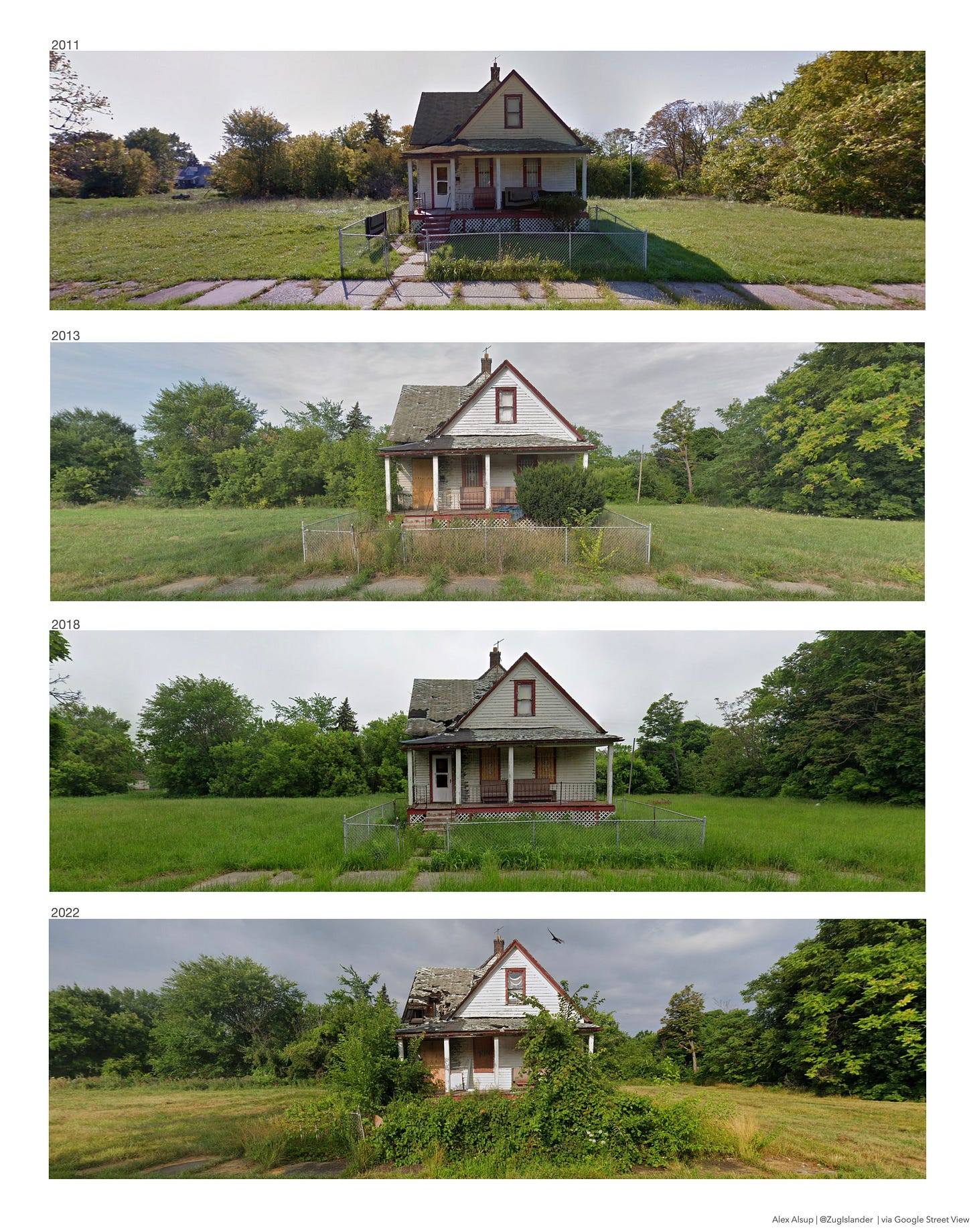

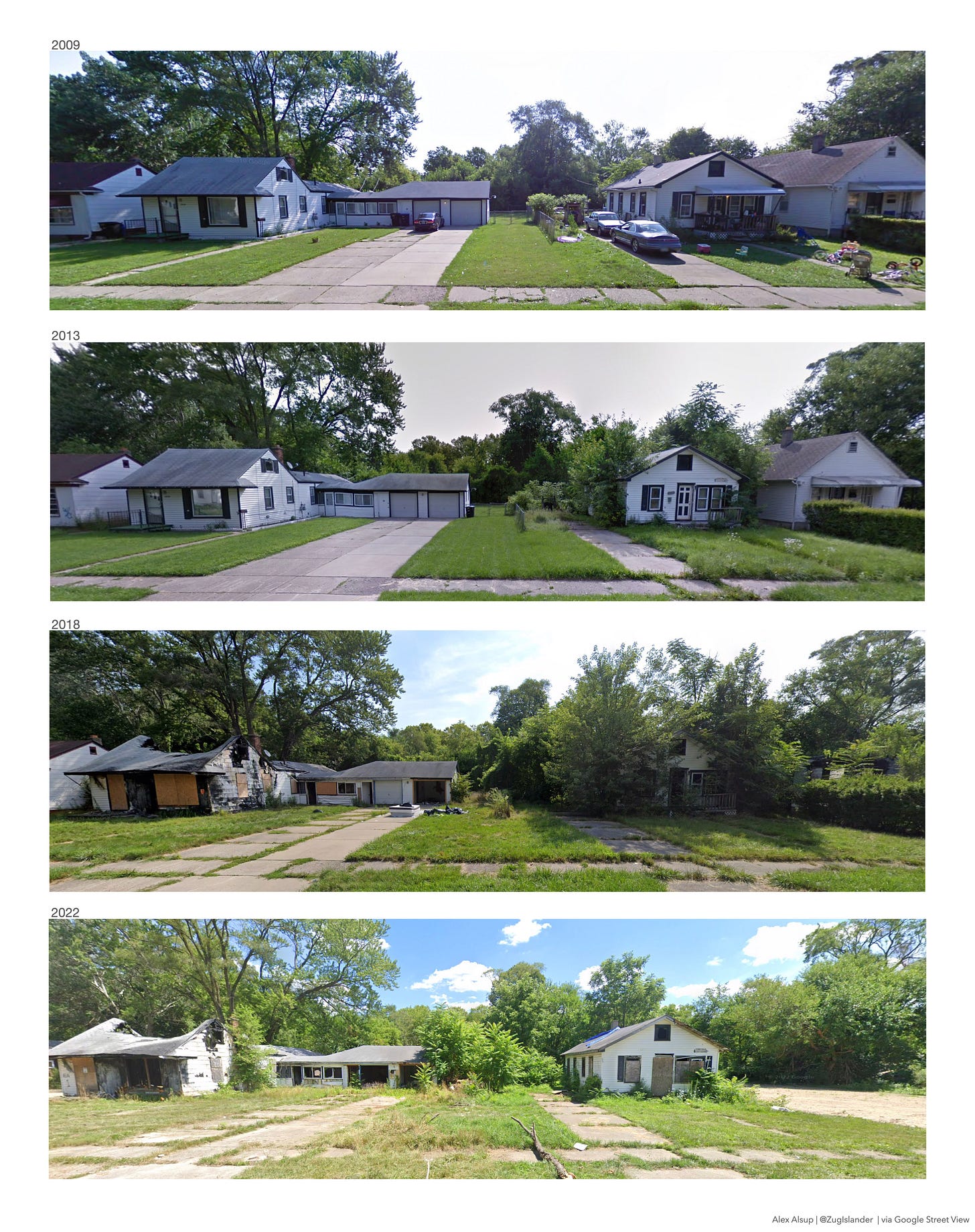

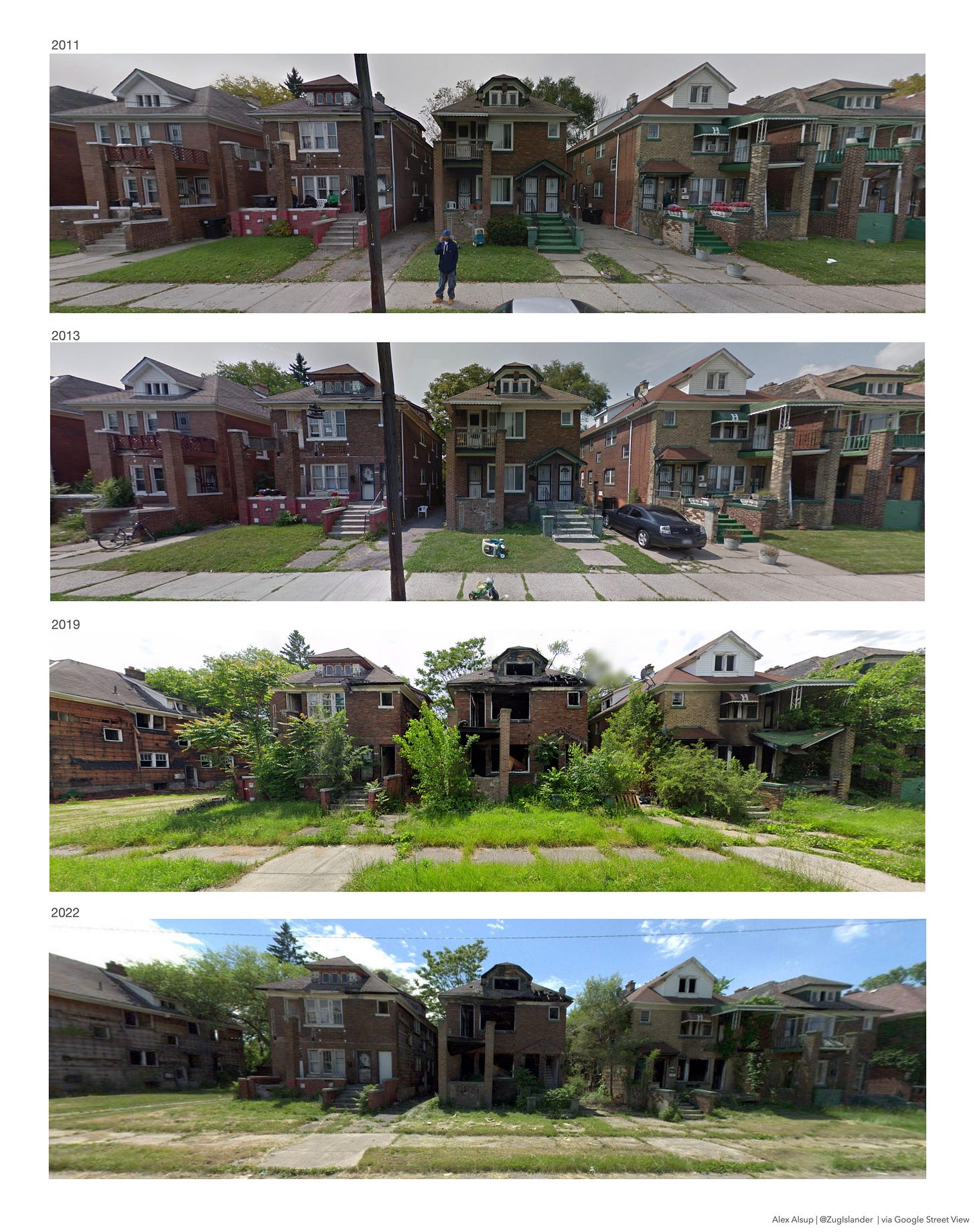

The imagery reflects many of the themes I’ve written about in the last year or so concerning Detroit’s neighborhoods amidst the pandemic: the efficacy (or lack thereof) of our massive demolition program, the rapid reactivation of long-vacant houses, and ongoing deterioration in some corners of the city. It is an incredible qualitative entry point to the far more complex governmental, economic, and social forces driving the changes in the imagery from year to year.

If you haven’t heard of GooBing before there’s some background on it at the end of this post. I’m also thinking about showing this series physically sometime this year in an exhibit, though no set plans for that yet. There’s so much important information reflected in the 2022 imagery that is distinct from the primarily tax foreclosure related topics I tried to address with the imagery from 2012 - 2019 — I think it would be worth trying to share that with people. I’d welcome any exhibit ideas in the comments or you can DM me on Twitter.

Demolition

Demolition is often praised, in part, for removing eyesores from a neighborhood. But Google Street View Time Machine imagery shows just how recently many of those “eyesores” were active homes with people sitting on the front porch, well-maintained lawns, and stark signs of people struggling to hang on. Awareness of the waves of tax foreclosure and eviction in Detroit over the last decade or so makes you realize how far from inevitable those eventual demolitions were, had different policy decisions been made.

In June I published a piece on the demolition program in Detroit called “An Epidemic of Blight Collides with a Pandemic”. I showed how, despite millions in demolitions funds and thousands of demolished homes, there were no fewer vacant homes in Detroit’s 48205 zip code at the start of the pandemic in 2020 than there were when the contemporary demolition program started in 2014.

Reactivation

In December of 2021, I wrote a Twitter thread detailing research I’d put together on a surge in long-vacant Detroit homes that had been rehabbed and reoccupied amidst the pandemic. During drives around the city that fall, I’d noticed homes in parts of the city that would never have been considered for rehab just a few years earlier that were now occupied homes.

Though an encouraging trend at first glance, behind the apparent revitalization are some concerning facts.

First is the fact that many of these homes were, until very recently, owner occupied homes that Detroiters lost to tax foreclosure and are today owned by investors or speculators outside the city. I wrote about that dynamic in a piece called “Bids on Detroit” which sought to quantify how much wealth had been transferred from Detroit homeowners to outside the city owners.

A second consideration is where ownership of these now-reactivated homes sits, and who is behind it? This is a topic I want to get into more this year but, as a start, take a look at this Felt map I made with data from Regrid showing Detroit homes in the Denby & Yorkshire Woods neighborhoods that are owned by a person or business in Florida. Nearly a tenth of the neighborhood homes’ ownership sits in Florida — I suspect this is a fairly new development. I plan on researching this more in the weeks ahead.

Open Question

The era in which Detroit neighborhoods were reshaped by tax foreclosure is, I think, over. It lasted from around the time of the financial crisis through the start of the pandemic. It could return, I suppose, but I’m optimistic that it won’t. Still, there are vacant homes languishing that have histories of tax foreclosures, evictions, or both. Whether the pandemic-era surge in rehabbing vacant homes continues, or eager bulldozers get to them first, we’ll see. I wrote about the diminished auction last summer.

Background on GooBing Detroit

It was back in 2012 that I started comparing images of Detroit homes captured by Google Street View circa 2009 with images of the same homes in 2011/12 captured by Bing’s Street View equivalent, Streetside. This was before Google Street View Time Machine, so I had to make do with the slight gap in capture dates between Google and Microsoft.

I was stunned by how quickly the financial crisis and the beginning of the tax foreclosure crisis were gutting the city’s neighborhoods — fast enough that just a couple years’ difference in street view vintage began to capture the deterioration.

Given my mashup of the Google and Bing’s street view services, I began collecting the imagery under the name “GooBing Detroit”. In retrospect, it’s a dumber sounding title than the project probably deserved given how much value I’ve found in the imagery over the years and the reach of the images at times.

During Detroit’s bankruptcy trial, images from GooBing Detroit were presented as evidence during Dan Gilbert’s testimony (I only found out after the fact, via Twitter).

Around 2014, Google released its Street View Time Machine function and, since then, I’ve primarily relied on that for the photographs in the GooBing series. More recently, the City of Detroit launched its own street view collection project which they publish via Mapillary. It’s a wonderful project, the imagery is great, and I’ve used some of it in areas where the City of Detroit’s car has driven more recently than Google.

Though it’s less present today, there has been sensitivity and criticism in recent years for photography of Detroit’s contemporary decline. The term “ruin porn” can make anyone looking at images like that of GooBing Detroit feel like they’re doing something wrong. Contextless gawking at the city’s difficulties is cringeworthy, no doubt. But I think that any honest curiosity and interest in learning about what’s happened in Detroit, and what it can teach us about the rest of the country, has to start with, to paraphrase my friend Chuck Marohn of Strong Towns says, “humility and observation.”

Hey Alex - I'm an editor for The Conversation and I would love to use a photo from your Substack for a piece on razing in Detroit that I am working on. Could you please send me an email? Thanks in advance!

zack.newman@theconversation.com