The Profit Motive Will Remain (Redux)

New legal challenges are coming for Michigan's tax foreclosure system. But first, revisiting 2020’s Michigan Supreme Court decision in Rafaeli, LLC v. Oakland County.

There are new lawsuits coming for Michigan’s tax foreclosure system that I want to discuss in future newsletters. One of these suits comes from the Pacific Legal Foundation, which dealt a blow to the tax foreclosure system in 2020’s Rafaeli, LLC v. Oakland County. Before getting into the new lawsuits, though, I want to return to the Rafaeli case.

I think the impression many got from coverage of the Rafaeli case and decision is that Michigan county treasurer offices can no longer profit from the tax foreclosure system, and / or that county treasurer offices’ primary source of profit via the tax foreclosure system had been removed. That is, after all, what attorneys for the Pacific Legal Foundation suggested the case was about — removing the “perverse incentive” of county treasurers to make more from a tax foreclosure than they could from a taxpayer. But that’s not exactly what the Rafaeli ruling did.

What follows is a version of a much longer analysis I wrote at the time of the Rafaeli decision in 2020. In it, I sought to lay out where most profits in the tax foreclosure system actually came from in Wayne County in recent years, and why the Rafaeli decision wouldn’t change that.

I’ll link to the original, much longer piece in this newsletter, if you want to go deeper.

In 2014, Uri Rafaeli lost a home he owned in Southfield, MI to tax foreclosure because he’d inadvertently underpaid his property taxes by $8.41.

For that, the Oakland County Treasurer’s office foreclosed on his home and sold it at a tax foreclosure auction — pocketing around $24,000 in profit on the sale in the process.

In 2020, the Michigan Supreme Court delivered a landmark decision that ruled what the Oakland County Treasurer’s office had done (and, by extension, what county treasurers across the state had done to thousands of property owners over many years) was unconstitutional.

The court’s decision in Rafaeli, LLC v. Oakland County determined that government keeping the proceeds of a tax auction sale above the tax debt, interest, penalties, and fees owed, was an unconstitutional taking. The court said Michigan county treasurers must provide a way for property owners to recover those profits in the event their tax foreclosed property sells at auction for more than the debt owed.

My impression was that media coverage of the case as it moved through the courts was largely sympathetic to the argument against county treasurers profiting in instances where tax foreclosed homes sold for more than the taxes owed. No doubt the egregiousness of Rafaeli’s situation was difficult to defend.

As the attorney representing Rafaeli from the Pacific Legal Foundation, Christina Martin, put it in a 2019 Detroit Free Press article on the lawsuit:

“Because they are able to profit, the county does not have an incentive to avoid foreclosures,” said Martin. “Instead they actually have an incentive to foreclose on people even when they shouldn’t. And we want to change that.”

That argument would make sense if tax foreclosure auctions were the primary source of profit within the tax foreclosure system. But, at least in Wayne County, they’re not.

In Wayne County (and I suspect this is the same for many other counties across the state with higher rates of property tax delinquency, but I don’t have the same granularity of data to reproduce the analysis statewide) the vast majority of the profits (and they have indeed been vast at times) made by the county treasurer’s office do not come from properties selling for more than the tax debt owed at tax foreclosure auctions. Instead, they come from taxpayers falling behind on their property taxes and, then, paying those taxes late, plus 18% annual interest, per state law.

The right of county treasurers to charge and collect interest, penalties, and fees was not challenged in Rafaeli. As Rafaeli’s attorney, Christina Martin, said during oral arguments to the Michigan Supreme Court:

“Rafaeli… [is] not challenging the statutory interest or penalties or fees that are tacked onto their property tax debts.”

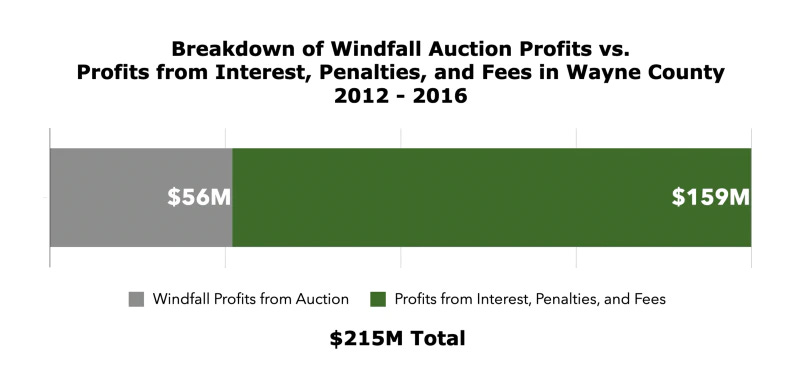

Below is an estimate I put together at the time of the Rafaeli decision showing how much the Wayne County Treasurer’s office made via “windfall profits” in tax auctions (where properties sold for more than the tax debt owed) vs. profits from taxpayers paying their property taxes late, plus interest, penalties and fees, from 2012 - 2016.

(In the piece I wrote at the time of the Rafaeli decision I have much more background on how I put these figures together. You can read that here, if interested.)

As you can see in the chart above, about 26% ($56M) of the Wayne County Treasurer office’s profits from the delinquent tax / tax foreclosure system between 2012 - 2016 came from properties selling at auction for more than the tax debt owed.

74% ($159M) came from property owners paying their delinquent taxes (or at least a portion of them), in order to keep their property out of a tax foreclosure auction, plus interest, penalties, and fees.

I would also push back on the idea that there is a clear incentive to put a property into a tax foreclosure auction. I can only run these numbers in Detroit (and I suspect there is more variation on this point across the state based on the strength of each county’s real estate market) but here, in the peak tax foreclosure years, it was at best a coin flip as to whether a tax foreclosed property in an auction would even SELL, let alone sell for more than the tax debt owed. Below is a chart looking at the number of Detroit properties that wound up in a tax foreclosure auction from 2005 - 2019, and how many sold vs. didn’t sell at all:

57% of the more than 156,000 tax foreclosed Detroit properties between 2005 - 2019 did not sell, even for the across-the-board minimum opening bid of $500 in the second round of all tax foreclosure auctions.

Looking at those figures, you might wonder how those $56M in “windfall profits” I mentioned above was even generated in Wayne County, given how many Detroit properties went unsold in the 2012 - 2016 auctions, recovering exactly $0 of the remaining tax debt owed. The answer there is the name of this newsletter: The chargeback.

The chargeback passes the loss from any uncollected delinquent property taxes on to the city in which the property is located, while the profit generated by a sale at auction is kept by the foreclosing county treasurer’s office.

The chargeback means the county treasurer can’t really lose money on a tax foreclosed property. That’s pretty solid downside protection. Still, if you want to take the most cynical view of the tax foreclosure system, I would argue the most perverse of incentives prior to Rafaeli didn’t lie in trying to sell a property for more than is owed in a tax auction. Rather, it was found in a property owner remaining in debt and paying interest.

Fortunately, there have been legislative changes in recent years that have started to chip away at this dynamic as well. Most notably via Pay As You Stay (PAYS), which created a way for low income homeowners to see their tax debt dramatically, and retroactively, reduced. But it is up to individual cities whether they opt in to offering PAYS or not. The Wayne County Treasurer’s website currently lists 17 communities in the county that have opted in to PAYS, and 26 that have opted out.