What is The Chargeback?

“In the evolutionary urban order, Detroit today has always been your town tomorrow.”

Coleman Young, mayor of Detroit from 1974 - 1994

My name is Alex Alsup, and I’ve spent ten years working on tax foreclosure reform in Detroit from a number of angles — software design, community organizing, policy development, philanthropy, parcel-level research, door-to-door canvassing, taking pictures of pictures in Google Street View (as above)…

Tax foreclosure is an illuminating detail — it has been a long-running local crisis in the city of Detroit, but also reveals issues of national importance about property, municipal finance, and the relationship between local government and its residents.

Across the country, many people think of the recent history of Detroit as an outlier — a unique and unfortunate fate to be avoided. But as our former mayor, Coleman Young, said in his autobiography, Hard Stuff, quoted above, Detroit’s issues aren’t unique. Detroit’s issues are America’s issues, we just got to them early. I think what we’ve seen in Detroit with tax foreclosure falls in that realm.

In The Chargeback, I’ll share research and analysis regarding property tax foreclosure and Detroit housing issues in general. I may not publish something on a regular schedule, as this is very much a personal side project (so don’t expect late breaking news or coverage of every tax foreclosure development) but when there’s something worth covering, I’ll try to be on it.

“Ok, but what is ‘the chargeback’?”

The chargeback is a pretty inside baseball term within the world of Michigan’s delinquent property tax system. I called this newsletter The Chargeback because the tax delinquency and tax foreclosure systems in Michigan are full of these arcane terms that denote mechanisms almost no one understands, yet are consequential to the lives of people across the state.

You may find understanding these terms helpful, or, you may find that you wish to unlearn these terms once you know them. I understand both positions.

Be forewarned: The term “chargeback” may well fall into the latter category, but I feel like I need to provide some explanation of it here…

Here’s a crack at explaining the “chargeback”:

The delinquent tax system, and tax foreclosure system, in Michigan is administered at the county level. Unpaid property taxes in cities are transferred to the county treasurer after each tax year, the county treasurer sells bonds to make the cities whole, and the county treasurer then has the responsibility to collect on the debt and repay bondholders.

That’s about the simplest way to put it. It gets a lot more complicated, though.

The delinquent tax system is something of a “heads I win, tails you lose” proposition for the county treasurer’s office who runs the process. County treasurers in Michigan who create a Delinquent Tax Revolving Fund (I’m not going to get into what that is now, but suffice to say it is a way to finance the delinquent tax system) are pretty well insulated from losing money on a property that owes delinquent property taxes but doesn’t pay their debt, yet the county treasurer’s office can also reap profits from property owners that do pay their debts.1

How is that possible? The chargeback plays a key role.

When a property owner doesn’t pay some or all of the property taxes owed to their city in a given year, that debt is transferred at the beginning of the following year to the county treasurer, whose job it becomes to collect that debt.

The county treasurer, because they’ve taken on the debt, sells bonds that represent the total amount of property taxes that the cities within the county didn’t collect in the prior year. The county treasurer then advances money to each of the cities in the county in the amount of their uncollected property taxes. This is meant to ensure that cities have the property tax revenue they need, while the job of collecting on the property tax debt and paying back the bondholders falls to the county treasurer.

Once that property tax debt is transferred to the county treasurer, generally speaking, one of three things can happen to extinguish the debt:

The property owner pays the debt in full (plus interest, penalties, and fees). In this case, any money collected above the debt owed (once any costs of handling the delinquency are paid for) is kept by the county treasurer. Given that delinquent property taxes start to accrue interest at a rate of 18% / year after about one year of delinquency, and the bonds that finance the delinquent tax system generally pay bondholders something in the range of 2.5% - 5% interest (at least in Wayne County, where Detroit is), the profit to a county treasurer’s office from a property owner paying their delinquent taxes after a couple years of interest racking up on that debt can be significant. For example, a delinquent property tax balance for a Detroit home (with address / owner info removed) where ~40% of the debt is interest & fees. Not uncommon:

The property owner fails to pay their debt in full and, after three years of delinquency, their property is auctioned and sold for MORE than the tax debt owed. This scenario recently underwent major changes due to the Michigan Supreme Court ruling in Rafaeli, LLC v. Oakland County. I won’t get into that decision here in depth, but the ruling said, in brief, that county treasurers MUST give property owners a way to recover the money above the tax debt owed in the event the property they owned sells at a tax foreclosure auction for more than the tax debt, interest, penalties, and fees owed. If the former property owner files a “claim of interest” and their property sells at auction for more than the debt owed, then the county treasurer keeps the portion required for the tax debt (plus interest, penalties, and fees) and the portion collected via the tax sale of the property above that amount is returned to the former property owner. If the former property owner doesn’t file a claim of interest, then the proceeds above the debt owed are kept by the county treasurer.

The property owner fails to pay their debt in full and, after three years of delinquency, their property is auctioned and sold for LESS than the tax debt owed, or, it doesn’t sell at all (and no tax debt is recovered via auction).2 This is the scenario that informs the chargeback. In the event the county treasurer collects LESS than the taxes owed for a property whose debt they’ve taken on, that loss is passed on to the city in which the property resides via THE CHARGEBACK. When a county treasurer goes to the bond market to sell a bond, it will tally up — on a property by property basis — the total amount of tax debt that the delinquent tax & tax foreclosure processes failed to collect for each city. It will report that amount in the bond filing as “the chargeback”. The county treasurer will keep the chargeback amount to make itself whole for the properties where it failed to collect the total debt owed. When the city transfers over the next year’s uncollected property taxes, the county treasurer will advance the city that amount, less the chargeback.

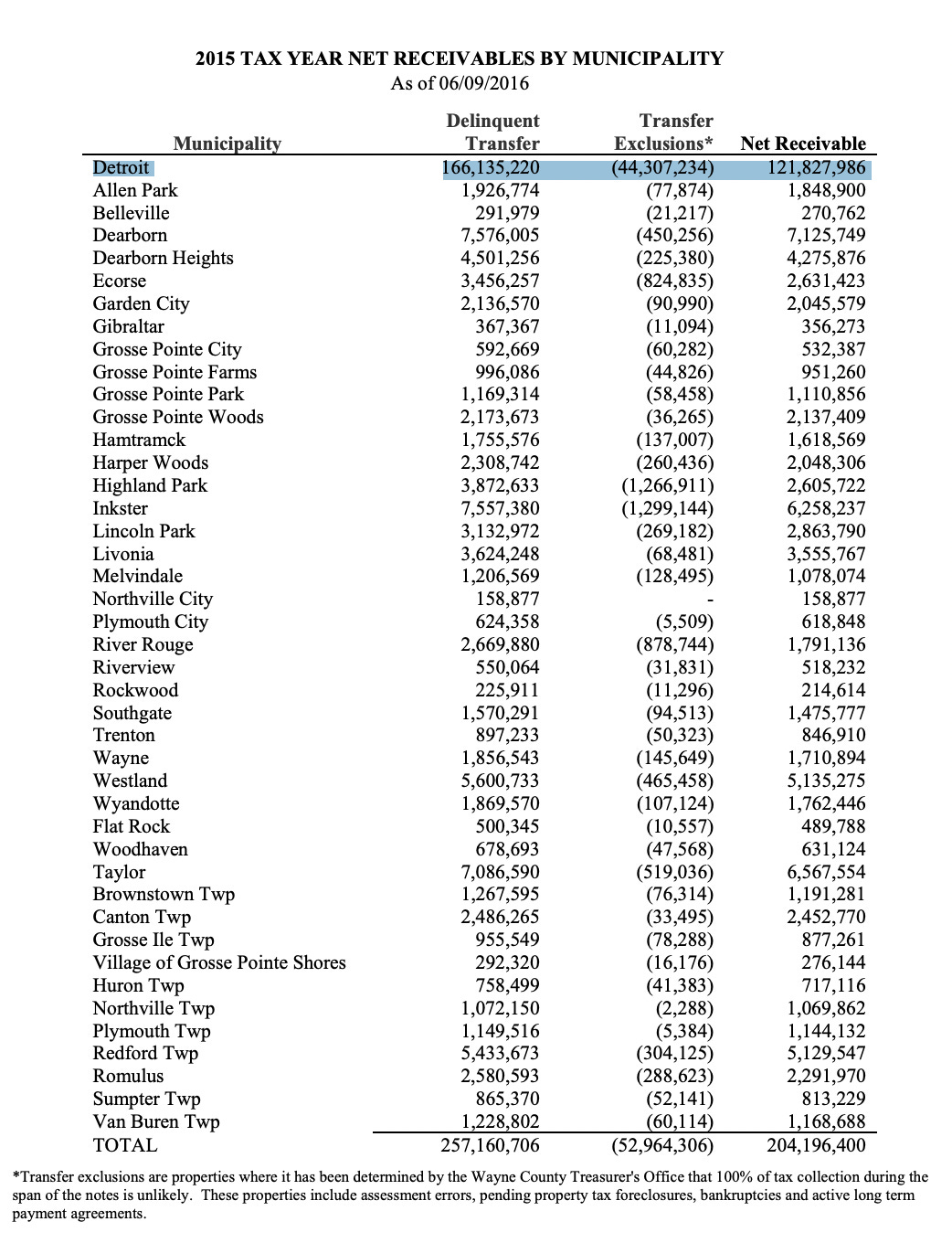

Those chargebacks, for the City of Detroit during the peak tax foreclosure years in 2010 - 2016 or so, could amount to tens of millions of dollars, meaning less money for city services. Here’s how the estimated chargeback (listed as “Transfer Exclusions” below) for the 2015 tax year for the cities in Wayne County appears on the 2016 bond filing from the Wayne County Treasurer:

In other words, for 2015, Detroit transferred $166M in uncollected property taxes to the Wayne County Treasurer. Of that $166M, there was $52M countywide that the Wayne County Treasurer determined unlikely to be repaid and would become that year’s chargeback, of which $44M (83%) would be charged back to Detroit.

And that is the chargeback.

Though Michigan’s delinquent tax system applies statewide, it can have variations from county to county. I’m going to speak specifically to Wayne County, even though this applies to many other counties across the state, for the sake of trying to simplify a very complicated system, and also to recognize that the very Wayne County-centric experience that informs my understanding of the delinquent tax system does not apply word for word to every county in the state and is specific to the operation of counties with Delinquent Tax Revolving Funds.

There are other scenarios that can inform the chargeback, such as properties getting onto certain payment plans, but I’m going to leave those out for simplicity’s sake right now.