Property Tax Delinquency Amongst Detroit's Lowest Income Homeowners is Vanishing

And with it, their risk of tax foreclosure

I keep sifting through years of property tax delinquency data collected by Regrid and feeling very optimistic about the progress eliminating homeowner property tax debt in Detroit since the start of the pandemic:

The years 2008 - 2019 in Detroit, from a housing perspective, were defined by tax foreclosures, evictions, and real estate speculation at rock bottom prices. I think that era closed with the arrival of the pandemic, the urgency of which created an opportunity for disparate programs, policies, and ideas to get serious and meet the conditions on the ground.

The pandemic brought many horrors to Detroit. A return of the heights of the tax foreclosure crisis could very well have been one of them, but it didn’t happen.

Detroit housing from 2020 - 2022 was marked by rising home values, a surge of rehab activity amongst the city’s vacant homes, and plummeting property tax delinquency. Where the housing ship took on water in the pandemic was amongst the city’s renters, which spurred a (halting) move towards right to counsel. I think the last few years will ultimately prove an interlude between the long crisis of 2008 - 2019 and whatever comes next.

There’s an opportunity right now to set the city up to engage with what comes next on different terms (as in, not sitting idly by, caught on our heels by whatever conditions arise). We’ll need to improve our collective powers of humble observation, but there are hopeful signs Detroit may capitalize on this opportunity. Split-rate tax, for example, would be a seismic shift and resetting of the terms of engagement concerning the city’s land.

There’s still property tax debt to eliminate, and there should be a very clear goal to wipe out every last dollar owed by Detroit homeowners. And I’ll be keeping an eye on the transfer of unpaid 2022 property taxes to make sure a wave of newly-delinquent Detroit homeowners doesn’t materialize. But I also want to look a little past tax foreclosure as a topic and write more about what comes next.

First, though, one more dive into the last few years of property tax delinquency data.

Progress from January 2020 to January 2023

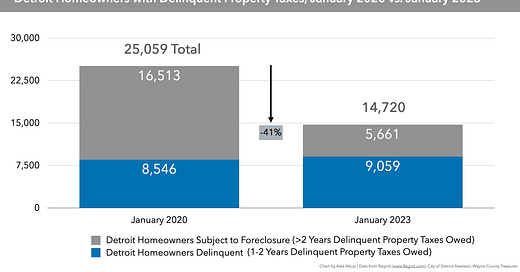

Between January 2020 and January 2023 the number of Detroit homeowners with delinquent property taxes fell from 25,059 to 14,720 — a 41% decline. Progress was even more significant amongst homeowners with more than two years of delinquent property taxes — those at greatest risk of losing their homes to tax foreclosure. Within that group, homeowner property tax delinquency fell 66% between January 2020 and January 2023:

The largest declines in tax delinquency are found in some of the lowest-income zip codes in the city:

In northeast Detroit, the 48205 zip code saw a 43% decline in homeowner delinquency since January 2020. No zip code has been more gutted by tax foreclosures.

The 48228 zip code, covering neighborhoods like Warrendale and Cody Rouge, saw more than 1,000 homeowners’ tax debt eliminated — 45% of the 2020 delinquency total.

In the 48210 zip code, where 2020 ACS data shows that half of residents speak a primary language other than English, 50% of homeowners with tax debt circa January 2020 had their tax debt wiped out, suggesting the language barriers may not be preventing the ability of residents to enroll in programs that can eliminate property tax debt.

The list of policies, programs, and organizations due credit for this progress is long:

Service providers like Wayne Metro, the United Community Housing Coalition, and community organizations across the city, programs like the City of Detroit’s HOPE exemption for homeowners in poverty, Pay As You Stay (PAYS) which wipes out ~70% of tax debt owed by homeowners who receive a HOPE exemption, and the Detroit Tax Relief Fund (DTRF) from the Gilbert Family Foundation which pays off the tax debt remaining after PAYS… and, far from least of all, the investment of trust and time from Detroit homeowners themselves.

All Tax Debt Does Not Disappear for the Same Reason

Detroit homeowner tax delinquency has, in fact, been declining for some time. Between 2014 and 2020 the number of homeowners with delinquent property taxes fell by about 50%, from just over 49,000 to the 25,000 figure in 2020 mentioned above.

The difference between the decline from 2014 to 2020 and the decline from 2020 to 2023 is that, between 2014 and 2020, reductions in homeowner tax delinquency were driven by thousands of homeowners being tax foreclosed out of existence.

Of the 24,000 homeowners removed from tax delinquency between 2014 and 2020, around 17,100 (71%) lost their homes to tax foreclosure, thereby eliminating their tax delinquency (and their homeownership):

Property Tax Delinquency Beyond the City’s Homeowners

While the declines amongst Detroit’s homeowners are the largest and most encouraging, it’s actually hard to find property types in Detroit where tax delinquency hasn’t declined since 2020.

Citywide since January 2020, the total number of tax delinquent properties (any kind of property — homes, vacant lots, commercial buildings, etc) dropped 12% and total property tax debt owed citywide fell 17% — from $212M (inclusive of interest, penalties, and fees1) in January 2020 to $175M in January 2023.

A similar decline is seen across Wayne County at large. Countywide (excluding Detroit) the number of tax delinquent properties fell 17% in the last three years, and cumulative property tax debt fell 10%.

An Exception to the Rule

One of the few exceptions to the rule of declining tax delinquency is found within a Detroit Land Bank program.

Per records from the City of Detroit’s open data portal on DLBA program sales, the number of properties sold through the Own it Now program increased from 3,301 through the end of 2019 to 9,690 through January 2023.

Tax delinquency data from the Wayne County Treasurer, via Regrid, joined to Own it Now program sale data shows that 560 of the 3,301 properties sold via Own it Now owed delinquent property taxes in January 2020 — 17% of all program sales. By January 2023, that number had grown to 2,530 Own it Now properties with property tax debt — 26% of all program sales.

While other DLBA programs, such as the Side Lots program and Auction program, also saw property tax debt increases, both kept pace with the overall growth rate of those programs: Debt levels increased in more or less lock step with program growth.

Not so with Own it Now, however, where program sales grew by 191% from January 2020 to January 2023, but the number of tax delinquent Own it Now properties grew by 351%.

Collectively as of January 2023, the 2,500 tax delinquent Own it Now properties owe $3.7M in property tax debt, an average of about $1,450 / property.

The Own it Now program is a way for the Land Bank to sell distressed inventory at very low cost — homes are listed for $1,000 via Own it Now. The expectation, as posted on Own it Now properties’ listing pages on the Land Bank website, is that buyers will have the homes either rehabbed and occupied or demolished within 6-9 months of purchase.

Rehab is a tall order for homes usually in seriously deteriorated condition with a “come one, come all” price tag, increasing the likelihood that unprepared buyers will violate a cardinal rule of Detroit real estate, coined by a friend of mine:

“DON’T BLIGHT OFF MORE THAN YOU CAN CHEW”

It’s always worth remembering how much the 18% annual interest added to delinquent property taxes by Michigan county treasurers inflates the appearance of delinquent tax totals. In Detroit, that $175M in delinquent taxes outstanding as of January 2023 is 29% interest, penalties, and fees. The face value of the tax debt owed, citywide, is $125M. If you also remove the portion of that debt owed by homeowners in poverty who never should have had to pay those property taxes in the first place, the $125M would fall to around $90M.

I will say it once here.

Stripping homeowners of their homes is a crime against humanity. It proves no one ever owns their property.

It also shows the cold, callous and backwards nature of taxing entities.

Each owner is a resident. That brings both state and federal per capita funds in. The owner buys things in the local economy, uses local services, pays utilities, etc.

Each resident is worth quite a bit to tax authorities.

Removing population often just redistributes liability to remaining tax payers.