Cutting Assessments Doesn't Necessarily Cut Property Taxes

Detroit City Council's call for 30% assessment cut wouldn't produce much in the way of property tax savings for homeowners

Last week Detroit City Council responded to a University of Chicago study that found the City is still overassessing low-valued homes. Council’s resolution called on the city assessor’s office to cut assessments for all owner-occupied homes with assessed values less than $17,500 by 30%.1

It might seem like a step towards significant property tax relief for Detroit homeowners with lower value homes. However, even if the assessor's office acted on Council's resolution2, my analysis shows only around 4,200 homeowners—just 3% of Detroit homeowners—would actually see their property taxes decrease. The average savings would amount to only $115 per year.

Working with 2023 Detroit assessment data3, I’ll explain why that’s the case.

Note: If you want a refresher on how & when cutting assessments generates property tax savings, take a look at the section towards the end of this piece titled Assessed Values and Taxable Values. I’m going to get right into the analysis here, but if you want some more detail on the mechanics involved skip down to that section.

The Proposed 30% Assessment Cut

According to 2023 assessment data, around 21,900 owner-occupied homes in Detroit—that's 17% of all owner-occupied homes—are assessed at less than $17,500. For a 30% assessment cut to translate into actual tax savings, the new, decreased, assessed value has to be lower than the home’s current taxable value — that’s the value the city uses to actually calculate your taxes. (Again, for a deeper dive into how this works, check out the Assessed Values and Taxable Values section below.)

So, the question is, how many of those 21,900 homeowners would have an assessed value lower than their current taxable value if their assessment was cut by 30%?

The answer: about 4,200 homes — 1 in 5 homes assessed at less than $17,500 — would pay less in property taxes after a 30% assessment cut.

On average, the property tax savings generated would be a modest $115 / year per home. You can see a breakdown of the number of homes that would see property tax savings, and how much they would save, below.

It’s not necessarily a bad thing that the impact would be minimal: Cutting assessments for low value homes by 30% and winding up with little in savings means that taxable values for these homes are already fairly low. That’s good — the average annual property tax bill across those 4,200 homes is $750 — but it’s not enough.

Exemptions, Not Just Reductions

If you pay attention to the actions of Detroit’s homeowners in poverty, the serious need is not for modest tax reductions but for 100% property tax exemptions. That is what the City of Detroit’s HOPE program (HomeOwner’s Property Exemption) offers to homeowners in poverty. The HOPE application can reduce or eliminate the current year’s property tax obligation for homeowners with low incomes. The vast majority of applicants receive 100% exemptions.

Looking at numbers from last year, the need expressed by Detroit’s low income homeowners is clear: around 1,500 property owners sought to lower their taxes through assessment appeals (that figure includes both homeowners and landlords), but an overwhelming 17,000 homeowners applied for the HOPE exemption.

Getting assessments right and helping homeowners (especially those not eligible for HOPE) file successful assessment appeals is important, but if City Council wants to meet the property tax needs of Detroit’s homeowners with low incomes, it has to come in the form of increasing the number of HOPE exemptions granted to homeowners in poverty.

Even at 15,000+ exemptions / year (a figure that has increased five-fold since the mid-2010s), we’re likely only reaching half the eligible population for HOPE. Additionally, as I wrote recently, we are starting to see some homeowners who have successfully used HOPE in the past lapse back into tax delinquency.

The successful utilization of HOPE is not a one-time fix, but an ongoing practice requiring monitoring and assistance due to the (reduced, but still substantial) difficulty of the application.

That’s why the focus of my years at the Rocket Community Fund were on working with dozens of Detroit community organizations to expand the HOPE application and make it retroactive to eliminate not just current tax obligations but property tax debt as well — it’s what Detroit’s homeowners need and deserve.

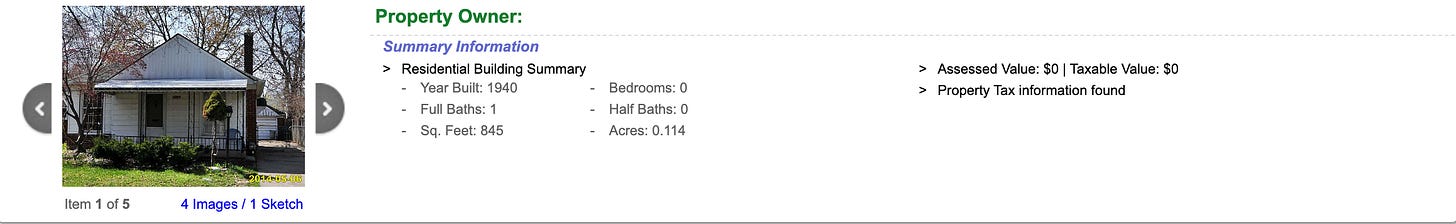

While wading through the city’s assessment website, looking at homes with assessed values less than $17,500 to verify my calculations for this piece, I stumbled upon a recurring and poignant detail: home after home with a taxable value of $0.

Why? They’d already received HOPE exemptions.

In an unassuming way, the city’s own, dry, assessment records paint a picture that shows the stark reality of what struggling homeowners in Detroit are calling out for.

If you ask Detroit homeowners in poverty what they want, they may well say “lower property taxes.” But if you take the time to observe what those homeowners do, you will see they are not seeking modest property tax reductions, they are applying for full property tax exemptions. That is where reform efforts should be focused.

Assessed Values and Taxable Values

A brief refresher on what the terms above mean and their relationship when it comes to a property tax bill:

When you want to reduce your property taxes, say by going to the Board of Review in February to file an appeal, you do so by appealing the assessed value of your home. Your assessed value is, in theory, 50% of market value.

Your taxable value is the value your millage rate (tax rate) is multiplied by, the result of which is your property tax bill. So, it is a reduction in taxable value that produces a reduction in your property tax bill.

The reason appealing your assessed value can lower your tax bill (even though your assessment isn’t directly a part of the equation that produces your tax bill) is that your taxable value cannot exceed your assessed value. That means an assessment appeal that produces an assessed value lower than your taxable value requires your taxable value to come down to equal your new assessment and, thus, gives you a lower property tax bill.

In other words: If you want a property tax reduction, the goal is to appeal your assessment and wind up with a new assessed value that is lower than your current taxable value.

Here’s an example:

Say you have a home with an assessed value of $25,000 and a taxable value of $17,500. If you appeal your assessment and the Board of Review cuts your assessment by $5,000, does your new assessed value of $20,000 yield any property tax savings? No, it does not, because it’s not less than your $17,500 taxable value.

Say, however, your appeal produces a new assessment of $15,000. In that case, your taxable value would also drop, from $17,500 to $15,000. You would then multiply the $2,500 reduction in taxable value by your millage rate (around 70 mills for an owner-occupied home in Detroit) to calculate your property tax savings: $175 / year.

Those are the basic mechanics we’re working with here.

Implying a fair market value of $35,000. The exact figure in the resolution was $34,700 but I’m rounding up to make the numbers a little cleaner.

I say “if” because cutting assessments by 30% on certain class of property within a certain band of assessed values would probably create issues with the state constitution’s uniformity clause. But I don’t really care about that one way or the other for my purposes here. I just want to evaluate whether the proposed cut would do anything meaningful, regardless of practicality.

The 2024 tax roll isn’t final yet, so numbers this year may be slightly different but probably not by much.

Math is merciless. It is sad that there is no coherent strategy to invest in these places. If you take a $20,000 home and have policies that turn it into a $22,000 home -- an extremely low lift -- then you've grown your tax base by 10%. If feels like the assessors should be part of the solution if they thought strategically and had a seat at the table. It feels like they go through the motions without much consideration for how important their work is.